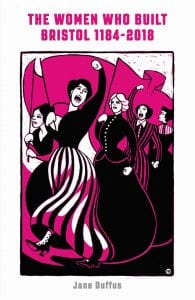

Guest blog by Jane Duffus (MA 2008), author of The Women Who Built Bristol, for International Women’s Day 2019

When asked to share some stories of amazing university women who make up some of the 250 entries in my book The Women Who Built Bristol, I was spoiled for choice. Which is a great problem to have. So rather than share some of the better known stories (of women such as Nobel Prize winner Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, registrar Winifred Shapland, or the university’s first female chair Helen Wodehouse), I’ve picked some women who are maybe a little more obscure… although no less magnificent.

Alongside Marian Pease and Emily Pakeman, Amy Bell was one of the first three women to earn a scholarship to the then-new University College, Bristol in 1876. Thanks to her university education, Amy went on to become a stockbroker. And while her sex made it impossible for her to work inside the London Stock Exchange, Amy set up an office close by and operated successfully from there.

Alongside Amy, was 17-year-old Marian Pease who, in the spring of 1876 had been due to sit the London University Women’s entrance exams… but an attack of scarlet fever got in the way. In compensation, her parents allowed her to apply for one of the three scholarships to Bristol. Describing her commute to the university, Marian wrote: “I left home a few minutes after eight o’clock carrying my heavy bag of books – there were no lockers there – walked across Durdham Down, met Amy Bell who came in a cab from Stoke Bishop and then we took the horse tram from the bottom of Blackboy Hill to the top of Park Street … The journey had its difficulties on dark, wet and windy winter mornings and afternoons.”

Marian later became Mistress of Method at the Day Training College on Berkeley Square. She took a keen interest in the girls she tutored and one wrote of her: “She was to us a new kind of person. Everything seemed turned upside-down as there unfolded before our astonished eyes a new and larger world of mind and spirit than any we could have imagined.”

Marian was inspired by Mary Paley Marshall, who was the first female lecturer at the University of Bristol in 1878 and co-founded the economics department with her fiancé Alfred Marshall; the progressive couple agreed to remove the word “obey” from their marriage vows to show their equality. Mary had already proved herself academically by being one of the first five students to study at the all-female Newnham College at Cambridge… although being a woman she was unable to graduate. However, this didn’t stop Newnham from later enlisting Mary as its first-ever female lecturer.

The Fry family were big players in Bristol owing to their successful chocolate factories, and Norah Fry was born into this dynasty. She went on to be one of the first female Cambridge scholars to graduate with the equivalent of a double first, and would become a founder member of the University of Bristol’s Council in 1909. However, Norah used her combined powers of wealth and education for good, and became a lifelong campaigner for children with disabilities and learning difficulties. The Norah Fry Centre for Disability Studies at the University of Bristol was established in 1988.

For more than 40 years, Dr Vicky Tryon cycled around Bristol doing her rounds. Vicky had been born in Bristol and attended the University of Bristol, where she became Woman President of the Union in 1919. However, she was far from a demure character. This is one description of a degree ceremony Vicky attended: “Singing and shouting interrupted the proceedings and on one occasion a hen was let loose to fly over the heads of the assembled students and dignitaries.”

Like other women who were attempting to forge careers in medicine in the early 1920s, Vicky was met with misogyny upon graduation. After applying for the post of House Surgeon at the General Hospital, Vicky was only offered the job if she promised to call one of the male doctors if there was any difficulty. It took 24 hours of hand-wringing before she reluctantly agreed. However, Vicky was to prove herself so capable and skilled in the role that the hospital then made a point of only appointing women to that position in the future.

You can buy The Women Who Built Bristol on Jane’s website. Volume two will be published in October 2019.